Nice to meet you all! I’m game designer Isao Negishi. Today I’d like to tell you guys about a storytelling seminar we designers at PlatinumGames received from none other than NieR:Automata director YOKO TARO!

Throughout his talk, YOKO-san demonstrated what he considers the essentials of storytelling through deep dives into specific examples. This information was extremely valuable – an understanding of these principles can be a creator’s asset for life. I could never cover everything we learned from YOKO-san here in this blog, but I’ll try to share the essence of what he said with you! His talk was organized around three points, which I’ll introduce now:

Emotions

To write a story is to design an emotional experience.

To do this effectively, you must start with an understanding of your own feelings. What is it that moves you? You have to identify and analyze the things that stir your own emotions. Then you can harvest those emotional elements and shape them into the parts of your story.

Worldliness

Each person is moved by different things.

When you write, you can’t assume that everything that tugs on your personal heartstrings will give the same emotional experience to everyone else. You have to keep all sorts of people, each with different sensibilities, in mind and present your themes from different angles to strike a chord with as many of them as you can.

Technique

Define the “emotional core” of your story: the feelings you want your audience to experience. As you flesh out your story, do so in a way that strengthens and accentuates this core. The emotional core is your absolute, top priority! Whenever you add something to your story, ask yourself how it reinforces the core.

That’s a very abridged version of what YOKO-san taught us. He spent a great deal of time going over each of these points with specific examples, making sure everything was clear.

Let’s say that, in actual practice, pretty much everyone starts off by analyzing their own feelings to some extent. But YOKO-san goes a few steps further; while watching movies at home, for example, he takes notes about what he feels, at the moment he feels it. Working on your craft during a movie feels like a pretty high-level technique, so it might be best to start off collecting your thoughts and emotional experiences after spending some time with a game or film. This analysis doesn’t have to be anything really formal – I get the impression that the important thing is that you do it, and keep doing it.

Speaking for myself, I got the impression that there’s actually a lot of overlap between writing game stories and doing game design. Game design demands that you thoroughly examine the games that you personally enjoy. The ability to synthesize gameplay structures and player experiences that are fun to you is a valuable game design tool. It’s also essential to put yourself in different kinds of players’ shoes as you create.

On top of that, the “emotional core” that YOKO-san describes at the center of a story is so similar to the role that a game’s “core concept” plays in game design that I’d venture to say they’re essentially two ways of describing one thing. At first I was surprised that there were so many points in common between these disciplines, but considering that YOKO-san has a great deal of experience as a game director himself, perhaps it only makes sense that his theory casts them in a similar light.

So really, YOKO-san’s seminar wasn’t just applicable to writing game stories. He offered a lot of meaningful advice for anyone involved in any creative work. We’re really grateful to him for sharing so much knowledge with us!

That concludes the report on his lecture itself – but there’s more! We spent the last half of our time with YOKO-san in a hands-on group workshop session! I’ll share a few photographs to give you a taste of what that was like…

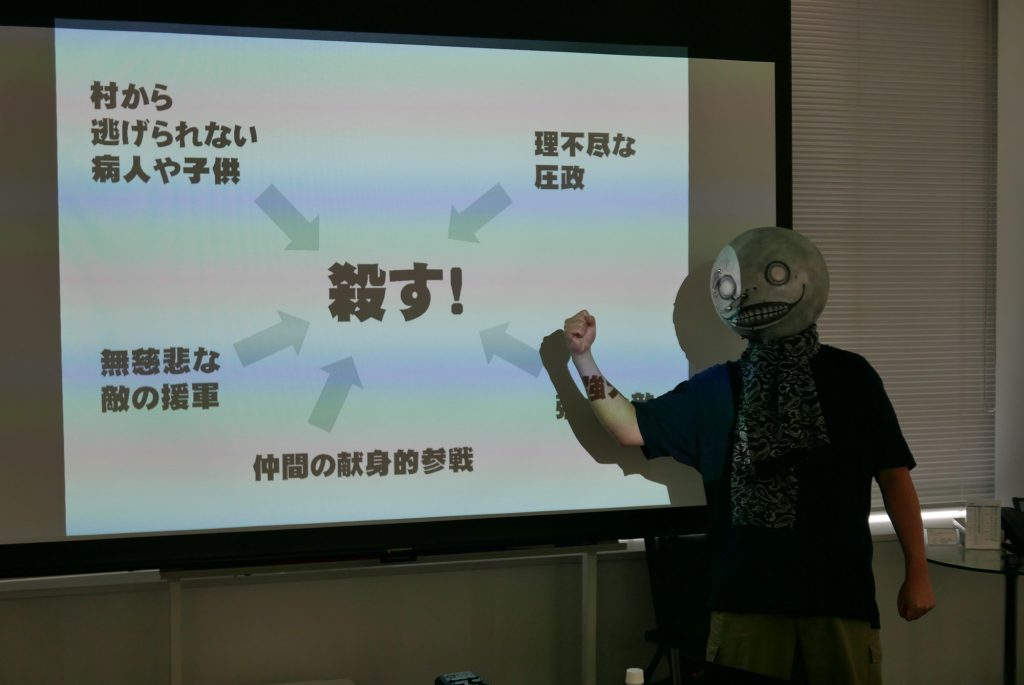

YOKO-san started by defining an emotional core for an action game where the player takes down hordes of enemies. That core is simple enough: “KILL!”

The next task is to work backwards from there, building the story up with elements that will make players want to fight and kill enemies: “They rule with an iron fist!” “Your allies are committed to the fight!” “The sick people and children can’t just flee your village to safety!” “Even more ruthless reinforcements are on the way!” and so on. (For the record, YOKO-san did not wear the Emil head for his entire lecture!)

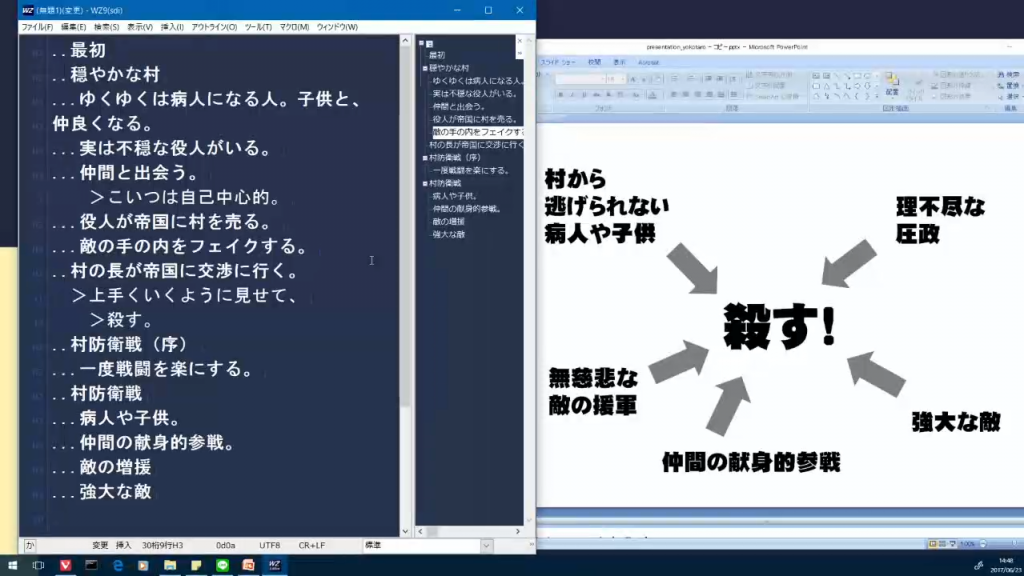

After adding these elements, YOKO-san put together a story prototype right in front of us. He added events into the story’s timeline to create a narrative flow towards the goal set by the emotional core.

After this blog post went online, YOKO-san got several requests from readers to go into a bit more depth on how he incorporated his buildup elements into this example storyline. He took to Twitter to provide some more specific information that we’d like to share with you now.

- Let’s we’re making a game about waging a defensive war to protect your village from enemies. Defeating and killing enemies isn’t exactly new ground for a game to cover, so we can start off with “Kill!” as our target emotion. There it is in the middle.

- However, just placing a few enemies around the map doesn’t necessary make players want to kill them. Let’s come up with some better reasons.

- First off, the enemies have to be jerks, right? Let’s say they’re oppressing the people of the village who’re just trying to live in peace.

- Beating up weak enemies makes you more of a bully than a hero, so these enemies have to be really fearsome and powerful.

- Humans tend to have some sense of heroism – they’re willing to give something their best shot as long as it’s for the sake of others. Let’s appeal to that with some weaker folks to protect. Boom, we’ve added children and sick people who can’t just pack up and leave their village. Now players have a deeper connection to the village and a stronger motive to fight for it.

- The game won’t be any fun if the enemies don’t put up much of a resistance. We’ve got to lull players into a false sense of security with easy foes as the game begins, then bring in some really ruthless enemy reinforcements as the story goes on. This gives us a chance to add new developments to the plot, and reinforces just how strong the enemy is supposed to be, too.

- Just as the player gets thrown into despair, they find some allies that’re committed wholeheartedly to their cause. I’m sure you’ve seen this before. Some NPC from the village, who didn’t even seem worth saving at first, steps in to say, “You have my sword!” These characters show the chivalrous resolve of the NPCs, which gets the player fired up in turn.

- Surely they’re feeling the “Kill!” spirit now.

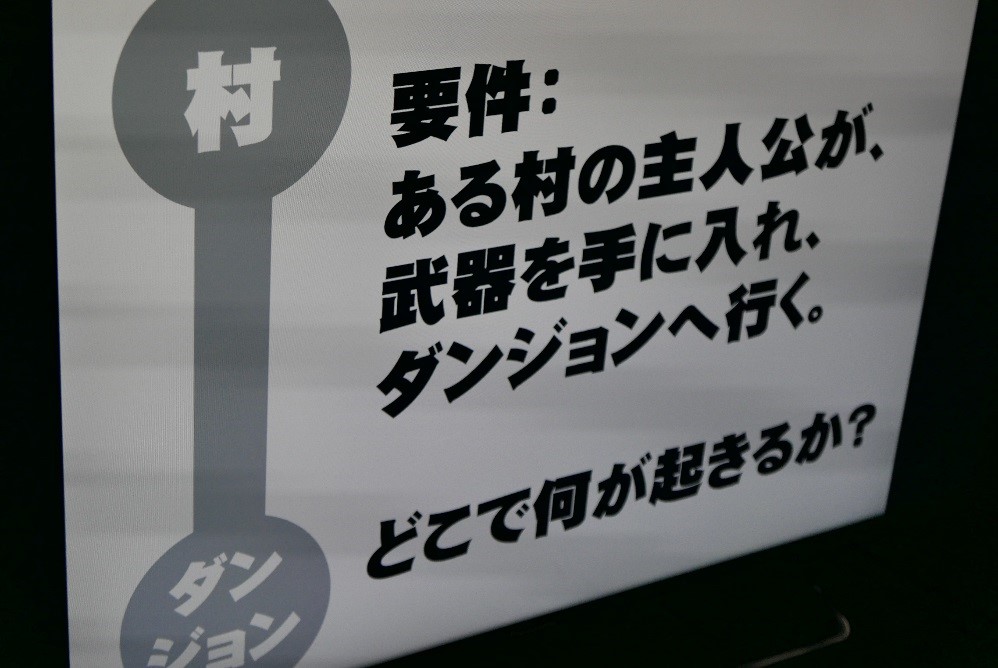

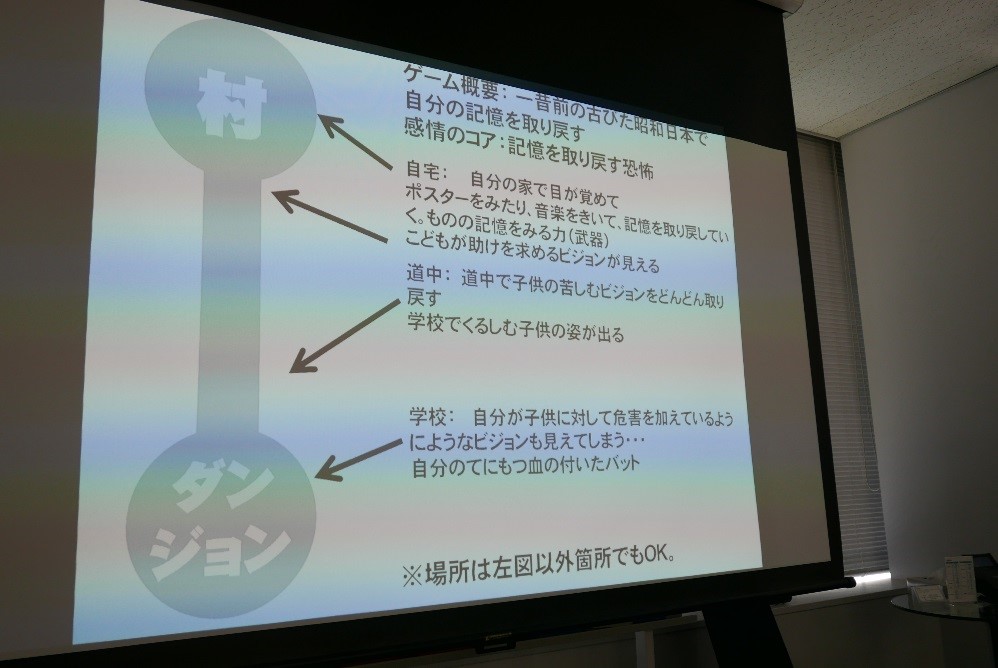

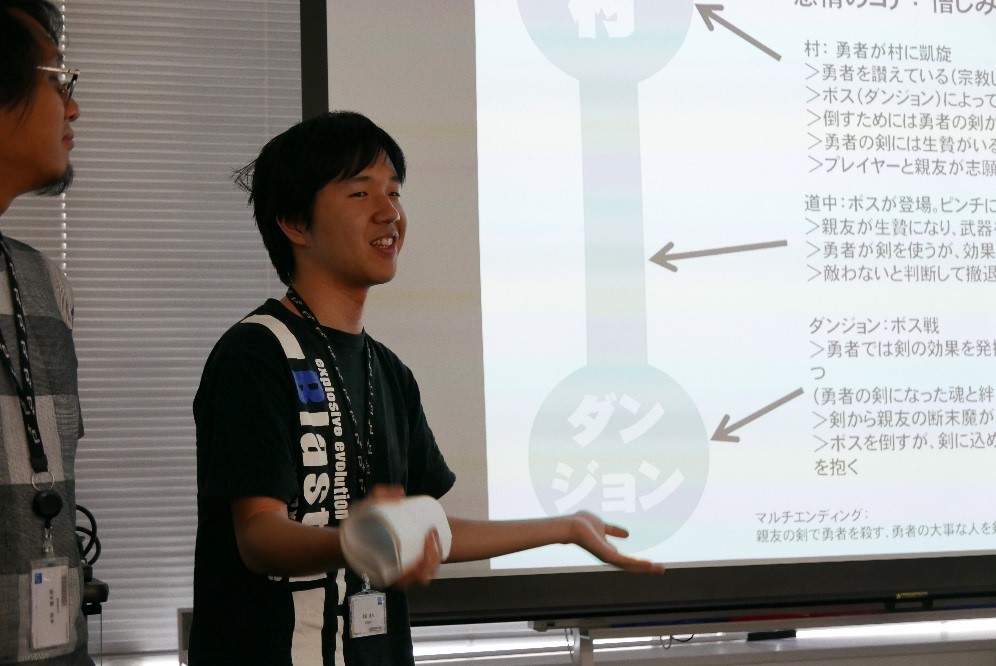

After a short break, we split into teams of five or six and worked together to create short plotlines ourselves.

FROM THE VILLAGE TO THE DUNGEON

- The main character is a villager who gets a weapon and heads to the dungeon.

- What happens when?

With YOKO-san’s presentation as a guide, we fleshed out our own plot structures.

As we tried putting our stories together, we ended up with a big jumble of story elements and a lot of questions about where to put which of them. It got pretty complicated!

It ended up taking nearly three times as long as we’d originally scheduled, but at last, each team brought their story to a (reasonably) complete form to share with the other teams. Last of all, we were lucky enough to get some very kind and constructive feedback from YOKO-san himself!

Isao Negishi

Isao Negishi

Isao Negishi joined PlatinumGames in 2011.

Since then, he’s worked as a game designer on The Wonderful 101 and The Legend of Korra; directed the Wii U port of BAYONETTA; and filled a wide range of game design roles on the NieR:Automata team, from level design to story implementation to subquest creation.